He glared at me for decades. You probably caught his eye too. He was one of this town’s most intrepid figures. It’s safe to guess that thousands of Kingstonians had their photographs taken with him.

Oddly, given his stature, he has no name, not officially, not yet. Anonymity was his fate from soon after the late Captain John Gaskin’s family donated him, in 1909. Originally he had a title plaque but it disappeared. Why will become apparent. Even so this defiant presence – an iron lion – stood sentry duty, facing south across Lake Ontario, for just over a century.

I don’t think any of the Captain’s descendants live among us but a few do rest in Cataraqui Cemetery and his likeness adorns City Hall. Why?

John Duerkop, a member of our Municipal Heritage Committee, has some answers. It seems Captain Gaskin’s father, Robert, was a ship owner of importance, evidenced by his stately ‘Parkview House,’ built in 1853 at King and Emily streets. A staunch partisan of the British Empire, his fleet included a barque christened the BRITISH LION. His son John, born 3 April 1840, worked the lake’s waves just like his father, a deckhand on the steamship SCOTLAND, later master of the RANGER, finally local manager for the Montreal Transportation Company.

Reportedly, John Gaskin made his presence felt in other ways. A zealous Orangeman, first president of the Protestant Protective Society, he flaunted his sympathies publicly by firing off the ‘Shannon Cannon’ on ‘the Twelfth’ of July, celebrating the Catholic defeat at the Battle of the Boyne and resulting ascendancy of Protestantism in northern Ireland. That cannon’s roar no longer disturbs delicate ears but it remains at hand, guarding St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church.

Several times alderman for the Victoria and Cataraqui wards, Gaskin was elected mayor in 1882, with the largest majority in the City’s history to that date, explaining his portrait near Memorial Hall. His anti-Catholic bigotry probably accounts for why the lion’s plaque was filched soon after it took up its post just north of the Richardson Beach pavilion. Gaskin was not everyone’s cup of tea.

When he died, in 1908, no Ukrainians lived here. Oral histories suggest a few arrived by 1910, so Kingston’s Ukrainian community marks its 100th anniversary this year. It’s doubtful Gaskin knew them. However, from reading the newspapers of his day, many steeped in anti-eastern European prejudice, he would know ‘men in the sheepskin coats’ were being lured to Canada with promises of freedom and free land. Generally, they were regarded as racially inferior, poor quality scaffolding for nation-building, a job best left to supposedly superior British-Protestant stock – just the sort of men Gaskin counted himself among.

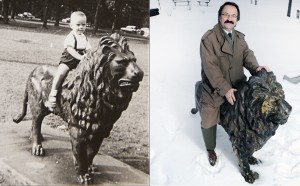

The Captain was long gone when I arrived, his lion just a marker where Ukrainians met for Sunday picnics after church. True, anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments persisted, but my boyhood friends included Catholic and Protestant lads, like Brian O’Brien and Bruce Wilson. Whatever their forefathers’ biases were we kids discarded those quickly on our playing fields. And the Orange Order meant nothing, even if I took ballet lessons from Mrs. Evelyn McDonald in their Princess Street hall. A photograph from the time, yours truly as the Blue Bird in Sleeping Beauty, is not for public display. However one that is, taken circa 1956, features me astride the lion. Like others in similar photographs I look happy. Of course that was childish naïveté. My parents, refugees who fled a Ukraine ravaged by Nazis then occupied by Soviets, were hard-pressed making ends meet, even as they found opportunity and freedom here. Small wonder they named their children Lubomyr (‘Lover of Peace’) and Nadia (‘Hope’).

It’s apt that we frolicked around an imperial relic. Whatever its faults Great Britain’s political legacy includes respect for the rule of law coupled with a commitment to parliamentary government and civil liberties. While some of the first Ukrainians in Kingston were internees at Fort Henry, jailed not because of anything they did but only because of where they came from, the Canada that men like Gaskin made by implanting British traditions did evolve into a society that later gave Displaced Persons asylum. Over six decades after they ‘got off the boat’ (and they literally did) my parents remain grateful for what this country offered – just as John Gaskin’s father, an Irish Protestant immigrant from Ulster was, over a century earlier.

Gaskin’s statue endured the wear and tear that goes with 100 years of public service. Mustering the Ukrainian community’s resources we made repairing his lion our centennial project. On 9 July it returns to MacDonald Park. When that happens no one shall pretend that Captain Gaskin was anything other than what he was. Yet the Kingston of today is not the Kingston of his era. And we understand that Gaskin was a patriotic, entrepreneurial and devout family man who believed in looking after his own. So Kingston’s Ukrainians have conserved his statue and will restore its rightful name – “Gaskin’s Lion” – because we also take care of our own, in this case Captain John Gaskin, our fellow Kingstonian.

Professor Lubomyr Luciuk teaches at the Royal Military College of Canada