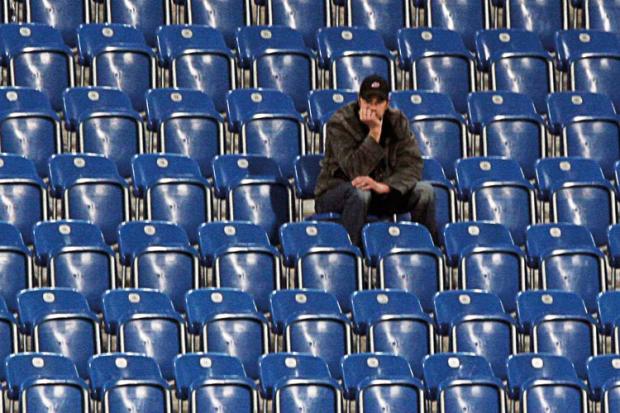

PhD students left feeling ‘dehumanised’ and ‘isolated’

By Holly Else

US academic urges sector to make doctoral students’ experience ‘more human’

Studying for a PhD can be “dehumanising” and “humiliating”, and programmes may be “needlessly isolating”, according to a US academic.

Scott Thomas, president-elect of the US Association for the Study of Higher Education, said that some universities were not doing a good job in terms of the postgraduate experience.

“A lot of the time when we talk about socialising graduate students we either focus on one or the other or we conflate the two in problematic ways,”

MORE…

He added that departments with the most eminent staff might be the most resistant to accommodating the changing needs of postgraduates in the current job market.

Professor Thomas, who is also dean of the School of Educational Studies at Claremont Graduate University, was speaking about academic socialisation and social support for postgraduates at the annual conference of the UK Council for Graduate Education.

“We don’t do a very good job of making the postgraduate experience a human experience,” he said at the event in Glasgow on 2 July.

“In some ways it is dehumanising, humiliating – it’s a challenge as it should be a challenging experience, but it is needlessly isolating,” he said.

Professor Thomas talked about the need for postgraduates to be socialised in two ways throughout their studies.

First, universities should educate them about the act of being a researcher and scholar, and second, they should provide support to help students understand the discipline and wider field within which they work, including related occupations.

“A lot of the time when we talk about socialising graduate students we either focus on one or the other or we conflate the two in problematic ways,” he said.

Across the world the academic labour market was “changing dramatically” with a heavier reliance on a “contingent workforce” comprising non-tenure or non-tenure-track staff, he added. “Many students are expecting to go out into the academy into positions much like ours, [but] the fact is that the opportunity for the assumption of those positions is declining,” he said.

Funding bodies and scientific associations in the US are now recognising this and are encouraging universities to introduce students to opportunities outside higher education.

“This is a pretty fundamental shift to what you were seeing even 10 years ago,” he said.

But shifting the emphasis of postgraduate research programmes towards industry will depend on changing the disciplinary norms and priorities of such courses.

These norms are set by faculty academics who hold dominant posts, such as presidents and board members of associations, and editorships of key journals, he said.

“It is in some ways a bet that those programmes that are strongest in terms of the faculty organisation and research organisation will have the most resistance to change,” said Professor Thomas.

In addressing these tensions, universities should question accepted competencies and modify them to reflect “non-academic realities”, he continued.

To tackle social isolation, universities should focus on the early part of postgraduate programmes and consider the importance of providing a physical space that allows students to interact. Academic advisers should also be trained to recognise the signs of loneliness.

“We have done a great deal of work on the doctoral student experience,” he said, but “very little” of that work had considered that there can be huge differences between programmes, universities and disciplines. “I think we need to pay attention to the complexity of those interfaces,” he added.