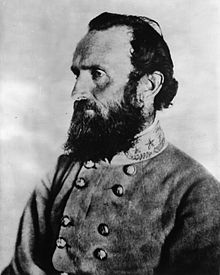

Morale Building Quotes from Stonewall Jackson:

“My men have sometimes failed to take a position, but to defend one, never !”

“Always mystify, mislead, and surprise the enemy of possible.”

“I yield to no man in sympathy for the gallant men under my command; but I am obliged to sweat them tonight, so as to save their blood tomorrow.”

“You may be whatever you resolve to be.”

MORE…

Stonewall Jackson was born in Clarksburg (then Virginia), West Virginia, on January 21, 1824. A skilled military tactician, he served as a Confederate general under Robert E. Lee in the American Civil War, leading troops at Manassas, Antietam and Fredericksburg. Jackson lost an arm and died after he was accidentally shot by Confederate troops at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Stonewall Jackson was born Thomas Jonathan Jackson on January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg (then Virginia), West Virginia. His father, a lawyer named Jonathan Jackson, and his mother, Julia Beckwith Neale, had four children. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was the third born.

When Jackson was just 2 years old, his father and his older sister, Elizabeth, were killed by typhoid fever. As a young widow, Stonewall Jackson’s mother struggled to make ends meet. In 1830 Julia remarried to Blake Woodson. When the young Jackson and his siblings butted heads with their new stepfather, they were sent to live with relatives in Jackson’s Mill, Virginia (now West Virginia). In 1831, Jackson lost his mother to complications during childbirth. The infant, Jackson’s half-brother William Wirt Woodson, survived, but would later die of tuberculosis in 1841. Jackson spent the rest of his childhood living with his father’s brothers.

After attending local schools, in 1842 Jackson enrolled in the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. He was admitted only after his congressional district’s first choice withdrew his application a day after school started. Although he was older than most of his classmates, Jackson at first struggled terribly with his course load. To make matters worse, his fellow students often teased him about his poor family and modest education. Fortunately, the adversity fueled Jackson’s determination to succeed. In 1846, he graduated from West Point, 17th in a class of 59 students.

Jackson graduated from West Point in the nick of time to fight in the Mexican-American War. In Mexico he joined the 1st U.S. Artillery as a 2nd lieutenant. Jackson quickly proved his bravery and resilience on the field, serving with distinction under General Winfield Scott. Jackson participated in the Siege of Veracruz, and the battles of Contreras, Chapultepec and Mexico City. It was during the war in Mexico that Jackson met Robert E. Lee, with whom he would one day join military forces during the American Civil War. By the time the Mexican-American War ended in 1846, Jackson had been promoted to the rank of brevet major and was considered a war hero. After the war, he continued to serve in the military in New York and Florida.

Jackson retired from the military and returned to civilian life in 1851, when he was offered a professorship at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia. At VMI, Jackson served as professor of natural and experimental philosophy as well as of artillery tactics. Jackson’s philosophy syllabus was composed of topics akin to those covered in today’s college physics courses. His classes also covered astronomy, acoustics and other science subjects.

As a professor, Jackson’s cold demeanor and strange quirks made him unpopular among his students. Grappling with hypochondria, the false belief that something was physically wrong with him, Jackson kept one arm raised while teaching, thinking it would hide a nonexistent unevenness in the length of his extremities. Although his students made fun of his eccentricities, Jackson was generally acknowledged as an effective professor of artillery tactics.

In 1853, during his years as a civilian, Jackson met and married Elinor Junkin, daughter of Presbyterian minister Dr. George Junkin. In October of 1854, Elinor died during childbirth, after giving birth to a stillborn son. In July 1857, Jackson remarried to Mary Anna Morrison. In April 1859, Jackson and his second wife had a daughter. Tragically, the infant died within less than a month of her birth. In November of that year, Jackson reengaged in military life when he served as a VMI officer at abolitionist John Brown’s execution following his revolt at Harper’s Ferry. In 1862 Jackson’s wife had another daughter, whom they named Julia, after Jackson’s mother.

Between late 1860 and early 1861, several Southern U.S. states declared their independence and seceded from the Union. At first it was Jackson’s desire that Virginia, then his home state, would stay in the Union. But when Virginia seceded in the spring of 1861, Jackson showed his support of the Confederacy, choosing to side with his state over the national government.

On April 21, 1861, Jackson was ordered to VMI, where he was placed in command of the VMI Corps of Cadets. At the time, the cadets were acting as drillmasters, training new recruits to fight in the Civil War. Soon after, Jackson was commissioned a colonel by the state government and relocated to Harper’s Ferry. After preparing the troops for what would later be called the “Stonewall Brigade,” Jackson was promoted to the roles of brigadier commander and brigadier general under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston.

It was at the First Battle of Bull Run in July of 1861, otherwise known as the First Battle of Manassas, that Jackson earned his famous nickname, Stonewall. When Jackson charged his army ahead to bridge a gap in the defensive line against a Union attack, General Barnard E. Bee, impressed, exclaimed, “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall.” Afterward, the nickname stuck, and Jackson was promoted to major general for his courage and quick thinking on the battlefield.

In the spring of the next year, Jackson launched the Valley of Virginia, or Shenandoah Valley, Campaign. He began the campaign by defending western Virginia against the Union Army’s invasion. After leading the Confederate Army to several victories, Jackson was ordered to join General Robert E. Lee’s army in 1862. Joining Lee in the Peninsula, Jackson continued to fight in defense of Virginia.

From June 15 to July 1, 1862, Jackson exhibited uncharacteristically poor leadership while trying to defend Virginia’s capital city of Richmond against General George McClellan’s Union troops. During this period, dubbed the Seven Days Battles, Jackson did, however, manage to redeem himself with his quick-moving “foot cavalry” maneuvers at the battle of Cedar Mountain.

At the Second Battle of Bull Run in August of 1862, John Pope and his Army of Virginia were convinced that Jackson and his soldiers had begun to retreat. This afforded Confederate General James Longstreet the opportunity to launch a missile assault against the Union Army, ultimately forcing Pope’s forces to retreat.

Against terrible odds, Jackson also managed to hold his Confederate troops in defensive position during the bloody battle of Antietam, until Lee ordered his Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw back across the Potomac River.

In October of 1862, General Lee reorganized his Army of Virginia into two corps. After being promoted to lieutenant general, Jackson took command of the second corps, leading them to decisive victory at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Jackson achieved a whole new level of success at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May of 1863, when he struck General John Hooker’s Army of the Potomac from the rear. The attack created so many casualties that, within a few days, Hooker had no choice but to withdraw his troops.

On May 2, 1863, Jackson was accidentally shot by friendly fire from the 18th North Carolina Infantry Regiment. At a nearby field hospital, Jackson’s arm was amputated. On May 4, Jackson was transported to a second field hospital, in Guinea Station, Virginia. He died there of complications on May 10, 1863, at the age of 39, after uttering the last words, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of trees.”

Source: www.biography.com.