Short CKWS video here

***

Governor General at the Citadelle of Québec – Presenting Medals & Awards

Among the recipients:

MERITORIOUS SERVICE CROSS (MILITARY DIVISION)

14596 Major-General Dean James Milner, O.M.M., M.S.C., C.D.

MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (MILITARY DIVISION)

16301 Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Christian Guy Leblanc, M.S.M., C.D.

21000 Captain Trevor Mark Pellerin, M.S.M., C.D.

15273 Colonel Gordon David Corbould, M.S.M., C.D.

B0178 Colonel Joseph Albert Paul Pierre St-Cyr, M.S.M., C.D.

16068 Brigadier-General Todd Nelson Balfe, M.S.M., C.D.

21473 Lieutenant-Commander Christopher Daniel Holland, M.S.M., C.D.

19173 Major Mohamed-Ali Laaouan, M.S.M., C.D.

17871 Lieutenant-Colonel Sean Patrick Lewis, M.S.M., C.D.

15678 Major Robin Kent Nickerson, M.S.M., C.D.

E2179 Lieutenant-Colonel James Robert Ostler, M.S.M., C.D.

18726 Lieutenant-Colonel Roch Pelletier, M.S.M., C.D.

19251 Captain(N) Ronald Gerald Pumphrey, M.S.M., C.D.

19420 Captain(N) Angus Ian Topshee, M.S.M., C.D.

15192 Colonel Peter Joseph Williams, M.S.M., C.D.

We tried cherry picking those names with a military college connection. If we missed anyone, sorry. Let us know. Write-ups here

***

25th anniversary of the Canadian Space Agency celebrated on silver collector coin

“This year marks a milestone in Canada’s space history as we celebrate the 25th anniversary of the CSA,” said General (Retired) Walter Natynczyk, President of the Canadian Space Agency. “Our many accomplishments have built the foundation for a flourishing space industry and we are absolutely delighted that the Mint has captured Canada’s leadership in space with such expert craftsmanship.”

12320 General (Retired) Walter Natynczyk – Article

***

Educating future Army officers about energy policy and climate change

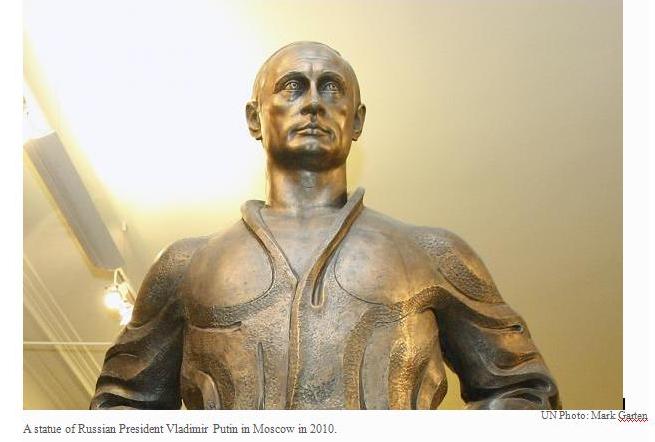

Inside Putin’s Mind

Originally published in Embassy News – embassynews.ca.

We need to understand better the world view and goals of Russia’s leader.

Yale University professor Timothy Snyder’s 2010 book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin deals with re-occurring devastating historical conflicts in East Europe. One might sadly add that, given recent events in Ukraine, an additional chapter might soon be needed.

Yale University professor Timothy Snyder’s 2010 book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin deals with re-occurring devastating historical conflicts in East Europe. One might sadly add that, given recent events in Ukraine, an additional chapter might soon be needed.

In a recent article, Snyder suggests that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggressive, ambitious style evokes a disturbing Orwellian quality when Putin proclaims that war is peace. Sadly, recent events and announcements seem to fit to a troubling degree an Orwellian dystopian vision for our future. Given Putin’s recent words and deeds, an increasing number of us just assume that Putin is always lying, distorting, deceiving or maliciously distracting.

He certainly revealed a skewed view of history when he claimed in 2005 that the break-up of the Soviet Union was the greatest geo-political catastrophe of the 20th century. What sort of amnesia did he possess about WWI and WWII? What kind of Moscovite leader would dare downplay the enormous Russian losses in those two world wars?

Perhaps the greatest tragedy for Russia is still to unfold. Putin may even play a major role. Certainly, his reckless and deadly actions are likely to significantly cost Russia, the region, Canada and the world. If a new prohibitive arms race unfolds, the meager peace dividends of the post-Cold War era will become a distant nostalgic memory. If conflict escalates and spirals out of control into a major regional war, it will certainly become a minus-sum game for virtually all.

To avoid such scenarios, we need to understand better the world view and goals of Vladimir Putin, along with the nature of Putin’s Russia that is emerging. For example, the centuries-old intellectual debate in Moscow between Slavophiles and Westerners still exists.

Are insular nationalist Slavophile goals once again displacing nascent and fragile Westerner aspirations of liberalization and greater openness to Europe? Is an authoritarian and somewhat lethargic bureaucratic state evolving once more into a more dynamic, ambitious and ruthless totalitarian regime? Or are we just witnessing yet another iteration of renewed would-be Tsarist ambitions, propped up by Russian Orthodox Church officialdom? Or is this, in essence, a ruthless KGB-recruited Bonapartist dictatorial regime?

A brief history

The West’s attempts to understand Russia have been an intellectual and diplomatic pursuit spanning several centuries. In 1939, Winston Churchill described Russia as “a riddle wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” In 1947, on the eve of the Cold War, George F. Kennan, the American ambassador in Moscow, penned a pioneering and pivotal piece in Foreign Affairs that provided the intellectual blueprint for containment theory and a string of US-based military alliances that encircled and sought to constrain the Soviet Union.

As Soviet military domination and tight political control over Eastern Europe took hold, an Iron Curtain of propaganda and massive censorship descended over these satellite countries. Stalin’s malevolent ambitions were accentuated by his ideological rhetoric.

The West responded in twin-fold fashion: economically the Marshall Plan to assist war-torn Europe was announced in 1947 and launched in 1948, while militarily NATO was formed in 1949 with the intention to stop the Russian army rolling westward. Canada played a key part as one of the twelve founding members of NATO, providing significant troops and fighter aircraft, particularly in the earlier decades. Today the alliance has grown to 28 member states, including the addition of a number of former Warsaw Pact states.

For much of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, the dominant paradigm for analyzing Russia was the totalitarian model. Its main features included a single all-powerful despotic leader who ruled through a single party, allowed only one official ideology, and made extensive use of state directed and controlled propaganda. It was a highly centralized coercive state that swiftly and brutally crushed all attempted political opposition. The model seemed to fit the Stalinist era.

Presciently, Daniel Bell penned an influential 1958 article explaining the search for different models to explain the dynamics of Russian society and the enigma of Kremlin decision-making. Amongst the frameworks that Bell suggested: the modernization and transformation of a once traditional Russian community; continued class rule, but in a new form; a highly formalized and centralized Russian bureaucratic polity; a despotic leader’s totalitarian control over all aspects of society; the continuation of Slavic cultural traditions, and geo-political imperial rule.

As the bipolar global Cold War receded and détente began to emerge first with Khrushchev in the 1960s and even Brezhnev in the 1970s, debates about appropriate strategy and tactics arose in the West. They involved not only the nature of the modern nuclear age and the ultimate motivations of the post-Stalinist Russian leaders, but also the appropriate framework for understanding a more modern Russian polity and society.

As Russians (both the public and leaders) became more urban, educated and affluent, had they begun to change? Had they become more moderate and even semi-pluralistic? The left wing in the West often suggested that important change had, in fact, occurred and thus prospects for peaceful co-existence were greater. In contrast, the right wing warned that the fundamentals of Russian society and politics had not changed, and accordingly we should remain vigilant, lest more dominos fall with the expansion of Russian influence around the world.

The rise of Gorbachev in the 1980s, with his policies of restructuring and openness, seemed to usher in a dramatic and positive change in Russia’s world view. Canada played a role in facilitating East/West dialogue, particularly during Gorbachev’s 1983 visit to Canada. However, with the rise of Putin from 1999 onwards, there has been an increasing concentration of arbitrary executive power in one person and strong re-assertion of Russian geo-political ambitions, reflecting an apparent desire to reverse the tides of history.

In 2014, events in Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and Armenia suggest that we are still confronted with major existential questions: What is the nature of Russian society and politics? What are the real foreign policy and military goals and motivations of Moscow’s leaders, particularly the increasingly dictatorial and mercurial Vladimir Putin?

It still seems that Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. It is also still a very dangerous world.