This is the conclusion of a four part series on the politics and people involved with the creation of the Royal Military College of Canada. It is taken from pages removed from the “Queen’s Quarterly 74, no. 3 (Autumn 1967), ” found in the shoe box of old photos in Panet House.

The Founding of the Royal Military College – Gleanings from the Royal Archives

By Adrian Preston

Modelled more on West Point than on Sandhurst but under imperial control until 1919, the Royal Military College, Kingston, from its establishment in 1876 offered a four year course designed to prepare students for civil as well as military employment, with salutary results and others less salutary.

Part 4

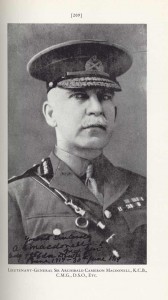

The decision to grant Imperial commissions to a limited number of Canadian graduates while preparing the majority for the various civil professions such as politics, law or business in which they later engaged, firmly established the pattern of R.M.C.’s contribution to the nation’s security and development for the next sixty years. If the original motive behind granting Imperial commissions had been to establish a sort of quid pro quo that would make it technically easier if not ethically proper to retain or reassert British military control over Canadian military affairs, it was certainly not ineffectual, although its side-effects were not altogether salutary. For thirty years, from 1874 to 1904, the G.O.C.’s Canadian Militia who worked unsparingly, often against heavy odds, to improve the national military condition, were British officers, some of no mean distinction. For over forty years, until 1919 when Major-General Sir A.C. Macdonnell became Commandant, the control of R.M.C. lay with the British Army. Infallibly and insensibly, from these and other things, there developed a process of conformity to British habits of strategic thought that was further intensified after the Boer War through the medium of the Imperial General Staff, and after the Great War by the practice of seconding Canadian officers to the War Office or sending them to study at the British Staff or Imperial Defence Colleges. The consequences for Canadian military development of this excessive reliance upon British concepts of strategy and professionalism could be only deleterious. It obscured the need for evolving any truly independent strategic concepts and doctrines and for constructing a local Canadian defence policy separate and distinct from that of Great Britain – a deficiency that inescapably committed Canada to fight according to a largely predetermined British strategy and plan in both World Wars. Similarly, it also prevented the development of an indigenous code of military behaviour and ethics applicable to Canada’s North American environment and social structure.

The decision to grant Imperial commissions to a limited number of Canadian graduates while preparing the majority for the various civil professions such as politics, law or business in which they later engaged, firmly established the pattern of R.M.C.’s contribution to the nation’s security and development for the next sixty years. If the original motive behind granting Imperial commissions had been to establish a sort of quid pro quo that would make it technically easier if not ethically proper to retain or reassert British military control over Canadian military affairs, it was certainly not ineffectual, although its side-effects were not altogether salutary. For thirty years, from 1874 to 1904, the G.O.C.’s Canadian Militia who worked unsparingly, often against heavy odds, to improve the national military condition, were British officers, some of no mean distinction. For over forty years, until 1919 when Major-General Sir A.C. Macdonnell became Commandant, the control of R.M.C. lay with the British Army. Infallibly and insensibly, from these and other things, there developed a process of conformity to British habits of strategic thought that was further intensified after the Boer War through the medium of the Imperial General Staff, and after the Great War by the practice of seconding Canadian officers to the War Office or sending them to study at the British Staff or Imperial Defence Colleges. The consequences for Canadian military development of this excessive reliance upon British concepts of strategy and professionalism could be only deleterious. It obscured the need for evolving any truly independent strategic concepts and doctrines and for constructing a local Canadian defence policy separate and distinct from that of Great Britain – a deficiency that inescapably committed Canada to fight according to a largely predetermined British strategy and plan in both World Wars. Similarly, it also prevented the development of an indigenous code of military behaviour and ethics applicable to Canada’s North American environment and social structure.

But the “civilian” as opposed to the British character of R.M.C. also contributed to this malaise. Its technical as distinct from a philosophical approach to the study of war discouraged the tendency of the Military College to become a great centre of strategic thought, research and scholarship as had Sandhurst under MacDougall and West Point in the days of Dennis Mahan and Upton. The exploits of great captains in great wars usually produce good theorists: but Canadian military history has experienced none of these. Admittedly, the bulk of R.M.C. graduates served for some time in the militia; but militia officers have notoriously been disinclined to concern themselves with the subtleties of strategic theory or rigorous analyses of prevailing defence policy. The only military theorist of international reputation that Canada has ever produced – Colonel George T. Denison – was a practising barrister and was inspired by the American Civil War to write his great treatise on cavalry. Thus after a century of national development, Canada still possesses no significant tradition of military literature, intellectualism or scholarship.

This otherwise deplorable situation has, however, not been without its blessings. There has never developed in Canada a nationalistic school of military history that could be accused of being the handmaid of militarism. We find no Clausewitzes or Treitschkes, no Seeleys or Mahans in Canadian historiography who have sought to create, propagate and sustain certain emotions or beliefs concerning national power, pride and loyalty on the one hand, and a flawless regimental valour and efficiency on the other. Until very recently, Canadian military history was regard, as Captain Cyril Falls once described it, as “one of the less attractive types of history, perhaps in a category approaching that of the history of prostitution, to be handed over to a handful of specialists, some of them suspect or even shady.” Unlike most military colleges elsewhere, R.M.C. had never been discredited as the hotbed of an uncompromising praetorian professionalism and a dogmatic doctrinaire approach to tactical and strategic problems. The course of Canadian life has been remarkably undisturbed by civil-military wrangling or conflict. The quest for Canadian sovereignty and autonomy, as well as identity, can be traced in terms not of military but of frontier, political and constitutional “myth-making”. All these things can be attributable in some small and intangible degree to the special character of R.M.C. as it was conceived by its founders and as it has largely remained.